- Home

- Charles Birkin

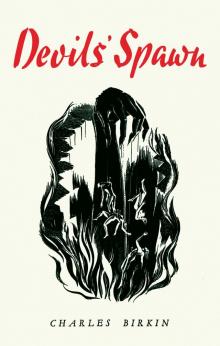

Devils' Spawn

Devils' Spawn Read online

DEVILS’ SPAWN

CHARLES BIRKIN

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Devils’ Spawn by Charles Birkin

Originally published in Great Britain by Philip Allan in 1936

First American edition published by Valancourt Books in 2015

Copyright © 1936 by Charles Birkin

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the copying, scanning, uploading, and/or electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher.

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

The Publisher is grateful to Mark Terry of Facsimile Dust Jackets, LLC for providing a scan of the dust jacket of the first edition.

To

WAVERNEY

for her

“ELOEE”

OLD MRS. STRATHERS

She sat in the rocking-chair before the grate of smouldering coal-dust, pressed and damped into a semi-solid mass so that it should burn the longer. Her eyes were bright with a quick nervous light that contrasted forcibly with the monstrous wreck of her face. For when the second stroke had fallen upon her two years previously, not only had all power of movement been taken from her, but she had also lost her power of speech, and was forced to live on, a powerless lump of suffering flesh, twisted and broken. Her body was shapeless in the many shawls that encumbered it. A tattered rug was wrapped round her knees in an endeavour to provide a slight protection against the chill of the poorly heated room.

Old Mrs. Strathers looked at the clock that ticked loudly on the mantelpiece, overcrowded with the ornaments and photographs so dear to her daughter-in-law’s heart. She peered into the greyling dusk. Six o’clock. Ronnie should be back soon.

Dear Ronnie! He was the one solace of her mockery of life, devoting himself to her on every possible occasion. But naturally it was only in the early morning and the evening that he could be with her. His office hours were long. Half-past eight until half-past six, with an hour off in the middle of the day. He was working too hard; and he hadn’t got the strength to stand it. Molly should have noticed it long since; and made him see a doctor. But no, the poor boy had grown to look worse and worse, until he was little better than a ghost; and it was not until the previous week that he had consulted a doctor—Doctor Hallam, who lived at the end of the street. Old Mrs. Strathers had never felt much confidence in him. Careless, and too fond of the bottle, in her opinion. Ronnie hadn’t told her very much of what he had said to him. She thought that he had made too light of it all, but that, no doubt, was because he was afraid of alarming her.

Eventually, the head clerk had told him he must seek medical advice; Mrs. Strathers remembered Ronnie telling Molly so. And she, his mother, was powerless to help him.

She looked at the clock. A quarter-past six. What could the boy be doing?

Flanking the clock on either side were two photographs in imitation silver frames. One of Frank, her second husband, dead these fifteen years; and one of her step-son, Charlie. Charlie was a chemist’s assistant in the High Street; and doing very well, so she’d been told. She slanted her eyes to the right, and could just see the coloured photograph of Molly, taken when she was engaged to Ronnie. It showed her with her head and shoulders bare, save for a wisp of tulle. Molly thought it very classy.

Old Mrs. Strathers sighed. Ronnie was such a dear sweet boy. She had been against his marriage from the first. A mother always knew when her son was marrying the wrong girl. And she had been right. She knew well enough that Molly and Charlie were carrying on—and they knew that she knew. And that was why they hated her so bitterly.

She heard a key in the lock of the front door. Ronnie, at last.

“Hello, Mother.” He came over to her chair and kissed her. “How are you feeling to-night, darling? Is there anything you want?”

They had an arrangement that if Mrs. Strathers was in need of something she should blink her eyes twice.

She tried to smile at him, but was unable to move her contorted mouth. Her eyes, alone, had a brighter light by which she showed her pleasure.

“No, dear?”

He sat down in the chair next to her, and lit a cigarette.

“I get my holiday at the end of the month—and then we can be together for two whole weeks. You’ll like that, won’t you, mother?”

He always told her of the daily events, and his future plans. He smiled at her.

“Molly’s not in yet, I see.”

Old Mrs. Strathers looked at his delicate hands. His sunken cheeks, marked with a hectic flush. His blue suit was neat, but much worn and very shiny at the knees and elbows. Molly, she knew, took every penny he made and yet was always in debt. Mrs. Strathers’ eyes grew hard as she thought of Molly. Taking Ronnie’s money, and living with Charlie under her very eyes! If she’d been Ronnie she’d have turned them both out of the house long ago. But Ronnie would never do that. He was staying here for her sake. He was too poor to support two homes, and it would mean the workhouse for her. The workhouse—that had been her spectre all her life.

Ronnie got up and walked into the kitchen. Soon he came back, a glass in his hand, a glass filled with a pink effervescent fluid.

“I haven’t forgotten my tonic to-night, you see!”

He swallowed it at a draught.

“Shall I make you a cup of tea, mother?”

Mrs. Strathers blinked twice. Ronnie was good to her. She was lucky to have such a son. She drank the tea that he held to her mouth greedily. It was her first nourishment since Ronnie had given her her breakfast before he went to the office. Molly had gone out at mid-day and hadn’t been back since. Yes—she was indeed lucky to have Ronnie to take care of her.

Old Mrs. Strathers listened intently. The door that led to the steep staircase was ajar. From time to time she could hear low laughter. But there had been silence for a considerable time, now. Charlie had come in about two o’clock. Molly was in the kitchen washing up the dirty plates from the morning’s breakfast. Her sleeves were rolled above the elbows of her wet red arms. Charlie had gone straight to the kitchen. There had been the sound of a faint scuffle.

“No, Charlie, don’t! Not now! Oh, you are a one!”

Then she had heard them kissing.

“Shut the door—do. She’ll hear.”

“What if she does? She can’t split on us!”

Charlie had given his coarse loud laugh.

They had stayed in the kitchen quite a while.

“Come on, Molly—leave that till later.” Charlie’s voice was urgent.

And then they had come into the sitting-room. Molly gave the old woman a look. “You and your Ronnie!” she taunted. “What good is he to a woman like me—eh, Charlie?”

Charlie had made a vulgar noise with his lips, and then they had both gone upstairs.

Old Mrs. Strathers had glared at them defiantly.

What could she do? Oh, what could she do? She thought of them standing there and sneering at her and her boy. Charlie, big and brutal, with his huge body and coarse face. And Molly, pretty still—in her common way. Where was all this leading? What was going to happen?

When Ronnie returned in the evening they had both gone out. He tried to entertain her with his news, but old Mrs. Strathers was inattentive. She must think of some way of letting him know what was going on—that his wife was a brazen hussy. A harlot. And they meant him an injury. She was convinced of it.

Ronnie saw that his mother was worried.

“What’s the

matter, mother? Are you feeling worse to-night? Tell me, what is it?”

He searched her face with his eyes.

“Headache?”

“No?”

“Are you thirsty?”

“Aren’t you comfortable?”

But all he could get in reply was the same intent stare. First at the photograph of Molly and then at Charlie’s.

“Does Molly want me? Is she ill? Is that what you’re trying to tell me?”

In the week that followed, Molly and Charlie treated Mrs. Strathers as if she did not exist. They carried out their love-making openly. She suffered their gibes and taunts, and was spared no humiliation. The climax came two days before Ronnie was due to begin his holiday. Once or twice Molly had noticed Ronnie looking at them curiously, and had surprised Mrs. Strathers giving significant looks, first at their photographs, and then at Ronnie; and what he had had so much difficulty in understanding was no mystery to her. Something must be done.

That evening when they had finished their supper Charlie said, “Like a cinema, Moll? There’s a good one at the Berridge Road.”

“Oh, that would be nice. I’d love it. Just a moment while I get my things on.”

She got up hastily and ran up the stairs to her room.

And they had gone off.

They were very late in getting back; for after the performance Molly turned to her lover:

“Look here! We’ve got to talk, I tell you. We’ve got to do something—and do something quick. I’ve thought of a plan, dear, but I need your help.”

“Well, we can’t talk here. Come on.”

They had walked for an hour, Molly talking eagerly, Charlie answering briefly; occasionally interrupting to ask a question.

When they returned to the house their minds were made up.

If Ronnie died, Molly as his widow would have the house and the furniture. And the old woman? Well, they could fix her all right.

The next evening Molly waited at the corner of the street where Bell and Brown, the chemists in which Charlie worked, was situated. She received many admiring smiles from men who were returning from their work, but she ignored them with exaggerated haughtiness. What could be keeping Charlie? she wondered. She turned and looked at herself in the mirrored walls of the shop-window into which she had been gazing. Smiling ladies of wax postured in peculiar and stilted poses, showing off the “Latest in Lingerie.” She pulled her small green hat lower over her eyes and fluffed out the fair hair over her ears. Then she applied her powder puff and lipstick—with more vigour than discretion.

“Hello, Moll. Sorry I’m a bit late. But I had to wait to shut up the shop. Useful that—what?” Charlie laughed, and pulling his tobacco pouch from his pocket, began to stuff his pipe.

“You’ve got it?”

Molly’s voice squeaked nervously in her excitement.

“In here, Love.”

He tapped his waistcoat pocket.

“Well, we’d better be getting back, I suppose.”

“What’s the hurry?”

He bent his head, and shielded the flame of the match. Over his pipe a look of understanding passed between them. She took his arm and together they mingled with the crowds on the pavement—a couple such as can be seen in their hundreds in any big town. Molly—pretty, cheaply but elaborately dressed; artificial silk stockings, high-heeled shoes, short skirt, gay pullover and “novelty” jewellery. Charlie with a bowler hat tipped at a rakish angle, brown suit, an impressive watch-chain from which dangled various charms and seals, and the swagger of a lady-killer.

But there the resemblance to their fellows ended, for there was murder in their hearts. Cold, calculating murder.

Mrs. Medlicott stood in front of the mantelpiece talking to, or, it would be correct to say, talking at, Mrs. Strathers. Her hands were on her hips, her pale eyes alight with interest in what she was saying. She enjoyed talking to Mrs. Strathers. At least, as she was constantly telling her husband, the old woman was a good listener.

“. . . And there she was, beating on the door. But her mother wouldn’t let her in, and quite right too, I says.” She finished with unctuous relish.

Old Mrs. Strathers fixed her eyes politely on her visitor.

“But I really must be going. It’s nearly time for Tim’s tea,” Mrs. Medlicott continued. “And by the way, I was sorry to hear that Ronnie’s been badly. Such a good boy, Tim and I have always thought, and such a good son, too! I hope that Mrs. Ronnie appreciates him as much as others do.”

There was a malicious thrust in this last statement, since Molly’s “flightiness” was common knowledge in the street.

“It’s his heart, I suppose. . . . I once had an uncle, poor man, who was took just the same way. He dropped down dead all of a sudden, one day. But then we’ve all got to die some day—it’s a short life but a gay one.” And with this singularly inapt observation Mrs. Medlicott patted her hostess on the shoulder, and went off to her own home, firmly convinced that she had been very charitable in cheering up “that poor old thing at Number Eight.”

But in spite of everything Mrs. Strathers was happier than she had been for a long time; for Ronnie’s holiday began on the following day, and she would have him with her all the time for the next two weeks.

Molly found it very difficult during the succeeding days to keep the excitement from her face. That the old woman suspected something she was certain. Her eyes never left Ronnie’s figure, unless to follow Charlie, or to watch with eager interest Molly’s every movement.

And so it was not until the following Monday evening that Molly found the opportunity for which she had waited. Charlie had gone to play billiards; and Ronnie was out for a short walk. It was seven o’clock. Molly had noticed that usually he took his tonic at a quarter past.

The sitting-room was empty save for Mrs. Strathers—watchful and alert.

Molly crossed to the shelf where the bottle stood, and emptied into it the contents of a tiny cardboard box she carried in her hand. A few of the crystals fell on to the shelf. Carefully she brushed them back into the box. She looked at the back of the chair where old Mrs. Strathers sat. She couldn’t have seen anything. . . . Then her eyes travelled past the old woman hunched in her chair, to the ornate mirror that hung above the mantelpiece. Mrs. Strathers was staring back at her with horror and mute rage. She had seen everything. Well—it couldn’t be helped.

“So you saw, did you—you old image,” Molly cried shrilly. “Thought it might be something to hurt your precious son, eh? You’re not far wrong either.”

She ran to the old woman’s chair and shook her roughly by the shoulder.

“And when he’s dead you’re going to the workhouse where you should have been long since—with your nosey-parker spying ways.”

She broke off as she glanced at the clock. Time she was off!

“See you later—you old idol.”

She slammed the street door and hurried away, her high heels tap-tapping on the pavement.

Old Mrs. Strathers waited for Ronnie to come back.

“I’ve brought you these violets, mother. There was a poor woman selling them in Civiter Street. Look—I’ll put them on the mantelpiece, where you can see them.”

His mother looked at him fixedly; imploring him to see the urgency of her appeal. Ronnie had his back to her, arranging the flowers in a small bowl of glazed earthenware.

“There!”

He bent down and kissed the top of her head.

“Now we’ll have a quiet talk before the others come back—but before I forget, I’ll just take my tonic.”

He picked up the bottle and measured out a dose.

“Beastly nuisance these hearts, aren’t they, darling?”

The muscles in Mrs. Strathers’ throat were taut in her effort to speak. Her face was suffused with a deep flush.

Ronnie drained his glass, making a wry face as he did so.

A terrible rasping croak sounded from the old lady’s chair.

Ronnie crossed the room in two strides, dropping the glass in his surprise. Splinters of glass sprinkled the linoleum on the floor.

“Mother—what is it?”

And then he felt the pain; at first in red-hot spasms, then more and more frequently.

“Mother—don’t be frightened—but—I think—I’m—ill.”

Doubled up in agony he clutched the edge of the table. The corner of the cloth was in his hand.

He fell to the floor. There was a crash as the crockery on the table slithered to the linoleum.

Ronnie was gasping; fighting for breath. His lungs laboured in the battle to draw in air. His eyes protruded, the irises turned toward the upper lids. A thick retching battled in his gullet.

He choked, twitched, convulsed with spasms, and lay still.

In the mirror old Mrs. Strathers saw his body, spread-eagled, and half shrouded by the tablecloth.

A quarter of an hour later Molly returned. She glanced quickly round the room, saw Ronnie lying on the floor . . . the splintered glass starring the oilcloth . . . the contorted attitude of the corpse. For a moment she waited, making sure that nothing had been overlooked. Satisfied, she hurried to the door, and half-staggered into the street.

“Mrs. Medlicott! Mrs. Medlicott!” Her shout echoed down the canyon of the houses. “Mrs. Medlicott . . . come at once . . . Ronnie’s been taken badly.”

Doors opened and heads were popped out of the windows. Soon a small crowd peered through old Mrs. Strathers’ door . . . attracted by the urgency of Molly’s cries. The heartless curiosity of the slums, determined to miss no atom of drama. Mrs. Medlicott ran from her house. She found Molly on her knees by Ronnie’s body. Instantly, gratified by being the centre of attraction, she gave instruction to the group of spectators.

“Get the ambulance . . . a doctor . . . Hallam from Number Seventy-eight.” A boy, eager to be of use, hurried away. “Not that he can be of much use. The poor boy’s dead as dead! I had an uncle what was took the same way, poor soul. Heart too, same as this one.”

Devils' Spawn

Devils' Spawn